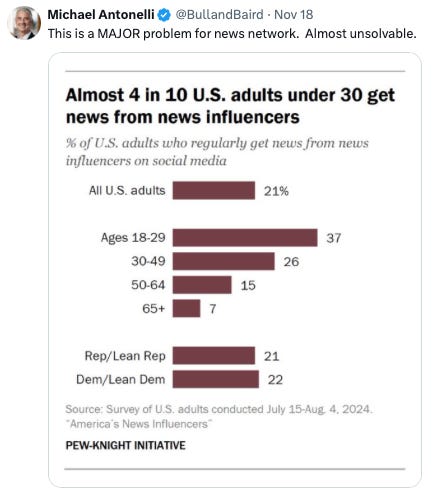

The collapse of trust in American media isn't just a crisis—it's a case study in market evolution. After decades of treating audiences as captive consumers, maintaining market share while trust plummeted, legacy media organizations now watch as the tide turns. Young Americans aren't choosing different news sources; they're reimagining what news consumption looks like entirely, gravitating toward individual creators who build direct relationships with their audiences—the rise of the independent.

This shift reveals a profound detail about how markets work: trust functions as a form of currency. When institutions deplete their trust reserves, they trigger a market correction as businesses and consumers reroute their attention and dollars.

This departure from traditional media platforms is about more than changing preferences. It's also about the market's remarkable ability to circumvent broken trust. The collective intelligence of the consumer, Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” drives an evolutionary outcome. In a market filled with competition and consumer choice companies either adapt to a new reality or they die slowly.

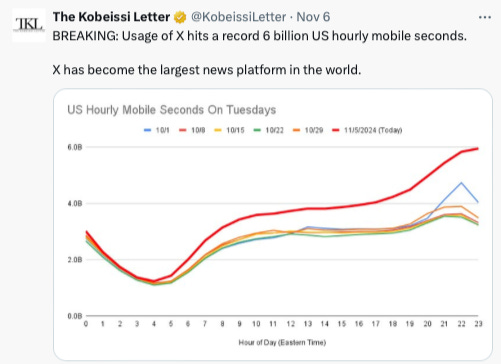

Social media and independent media is that new reality.

This trust-driven market correction in media reveals three key insights about modern economies:

Trust is a finite resource that institutions must constantly replenish.

When trust depletes in one sector, it doesn't vanish—it redistributes.

Consumer choice acts as a trust-verification mechanism at scale.

But here's where the story gets interesting: this natural correction process only works when markets maximize for consumer choice and are free to correct.

The media landscape demonstrates how markets naturally correct when trust breaks down: consumers redirect their attention—and dollars—elsewhere. But what happens when regulations prevent this correction mechanism from working? The American healthcare system offers an example.

Americans trust their doctors but deeply distrust the healthcare system as a whole. A 2023 Gallup poll shows 84% of Americans rate their personal healthcare quality as "excellent" or "good," yet only 48% trust the healthcare system itself.

Unlike the media landscape, where this trust gap triggered an exodus to alternatives, healthcare consumers remain trapped in a system immune to market correction.

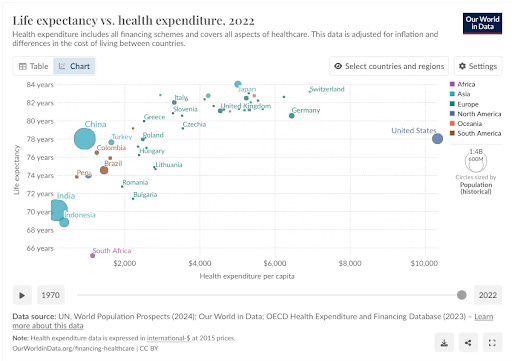

The chart above shows what happens when trust can't function as a market signal. While many industries become more efficient through competition and innovation, healthcare costs skyrocket while outcomes decline. The reason is structural: a complex web of regulations has created a system where pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers, and insurance companies negotiate with the government rather than compete for consumers. The opaque world of insurance, doctor’s offices, and hospitals leaves everyone confused, frustrated, and angry. You know you’re getting ripped off but just not quite sure how.

With the government as the primary customer—through Medicare, Medicaid, and regulated insurance markets—there's no incentive to respond to falling consumer trust. The government’s undiscerning demand short-circuits the market's natural correction mechanism while creating an unaccountable administrative state.

All the while, Americans have seen life expectancies drift lower while paying the highest costs compared to peers.

When trust breaks down in healthcare, policymakers typically respond with more oversight, more administrators, and more complexity. They try to regulate trust back into existence. However, as these charts show, this approach has failed spectacularly. Trust isn't built through regulation; it's earned through direct accountability to consumers.

David Friedberg from the All-In Podcast summarized things perfectly using the debate on whether the government should ban pharmaceutical companies from advertising on TV.

Friedberg points out that banning pharmaceutical ads on television hurts consumer choice and does not solve the root cause of the issue. Pharmaceutical and drug companies make hundreds of billions of dollars from contracts with the federal government that undergo zero negotiation. At the same time, rules and regulations have created hundreds of thousands of administrators and middlemen who add to the cost but do not improve outcomes.

The pharmaceutical advertising debate illustrates our core problem: we try to regulate trust into existence rather than allowing market forces to restore it naturally. When media companies lose public trust, consumers can easily switch to alternative sources—podcasts, newsletters, and independent journalists. However, in healthcare, government involvement has short-circuited this correction mechanism. Instead of competing for consumer trust, healthcare providers compete for government contracts and regulatory compliance.

Incentive, meet outcome. We don’t have a single-payer system or a free market. We have a captured market.

This pattern extends beyond healthcare. In higher education, government-backed student loans have short-circuited the trust-correction mechanism. When institutions know their funding is guaranteed regardless of performance, they have no incentive to earn consumer trust. The result? Skyrocketing costs and declining value—just like healthcare.

My point isn’t to eliminate all regulations. Instead, it's to design regulatory frameworks that maximize rather than block the market's natural trust-correction mechanisms. t

Stay trustworthy.

Jared